David Wheeler started his scientific career as a student and ended it as a professor emeritus of computer science. At first, he researched the programming problems of the newly invented computer. In the last years of his life, David developed algorithms for data encryption and worked on the elimination of email spam. Learn more at birmingham1.one.

David Wheeler’s meaning of life was improving computers. He designed the hardware and his programme codes were distinguished by “elegance”, as he omitted unnecessary lines and symbols.

The computer guru always cared about his followers and wrote several brilliant scientific works, which underlay the development of information technology in the world. Everyone who knew him noted that David was modest and hated management and bureaucracy. Therefore, he never held high positions and international success came to him rather late, after 50 years.

Interest in exact sciences

David Wheeler was born in Birmingham in 1927. His father was an engineer and owned a small company that repaired store equipment. The family lived in Small Heath, where David finished primary school. He inherited a love for engineering and mathematical disciplines from his father. In 1938, the boy received a scholarship to study at King Edward VI Camp Hill School. In 1940, the school was evacuated to the suburbs of Birmingham due to the Second World War. The move had an impact on David’s education, in particular, he had difficulties with learning Latin. Later, Wheeler joked that he didn’t become a writer because of his failure in language subjects. In 1942, the family moved to Tunstall. There, his father made aircraft tools and David completed the sixth form at the local school with honours in physics and mathematics. In 1945, on the recommendation of a teacher, David’s parents sent their son to Cambridge, where he passed the exams and won a state scholarship to study at Trinity College. Wheeler was successful at his mathematical studies and got a bachelor’s degree in 1948.

Mathematical laboratory and electronic calculator

Being a student, David attended the inaugural lecture of Professor Douglas Hartree in 1946. The professor had just returned from the United States and spoke about the development of an electronic computer by students at the University of Pennsylvania. The lecturer was convinced that the new devices would cause a revolution in science and mathematical calculations. After the speech, David Wheeler had no doubt about what he was going to do. The student turned to the mathematics laboratory at the university and impressed everyone with his enthusiasm. Scientists were developing their own computing device, which was officially called a calculator and commissioned by the UK Ministry of Defence. At first, David was assigned to do assembly and minor laboratory work, but later, showed his potential to the fullest. The first programme was executed in the spring of 1949. It calculated the squares of numbers from 0 to 99. The Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator (EDSAC) was officially presented to the public in June 1949.

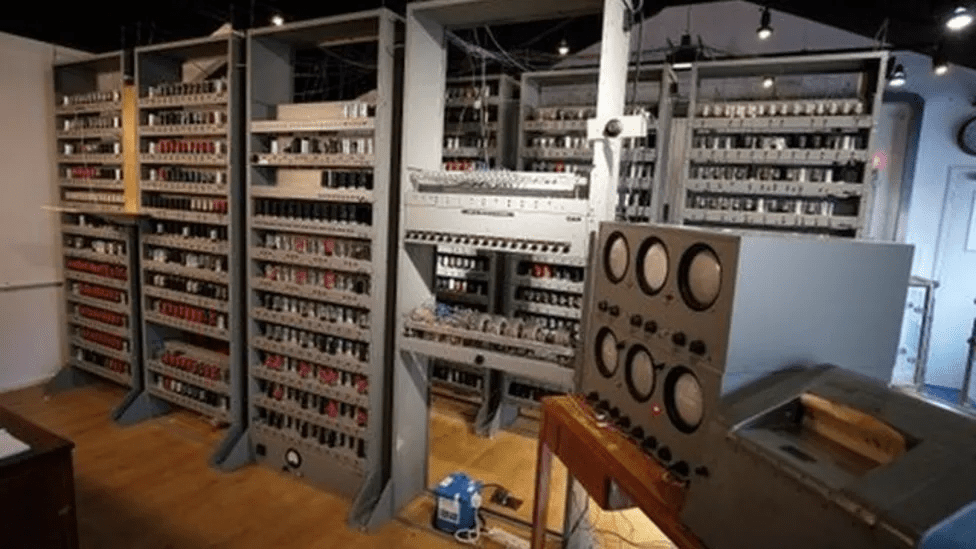

Some operational and technical characteristics of EDSAC

The computer consisted of 3,000 electronic lamps and 1,024 memory cells. It carried out calculations in the binary system (using zeros and ones) at a speed of 100 to 15,000 operations per second.

The computer had a power of 12 kW and covered 20 m². David Wheeler’s first symbolic-to-binary programme was 32 lines long. Throughout the history of computer science, software has always been an extremely difficult task. Therefore, when the EDSAC programming seemed to be under control, it always turned out that there was a bug. To reduce their number, Wheeler decided to use libraries, small subroutines, that could be included in the main user programme. Thus, he invented a closed subroutine. David spent the next few years writing library routines and building initial commands. Libraries of closed routines remain the basis of almost all programming systems. In 2003, Wheeler was inducted into the Hall of Fellows at the Computer History Museum in California for his seminal contributions to computer technology.

In 1951, David Wheeler and his colleague wrote the book The Preparation of Programs for an Electronic Digital Computer, which became the first programming guide for those who study computer science. The ideas they presented served as the basis for composition systems and were relevant until the early 1960s when the Fortran and Algol programming languages were created. In 1951, Wheeler defended his thesis and received a research fellowship at Trinity College. In 1952, David’s colleague A. S. Douglas created the first displayed computer game called OXO.

A new computer

The development of EDSAC 2 was launched in Cambridge in 1953. Wheeler was appointed head of the project. He worked on microprogramming that could combine the computer functions into one. David invented one-pass assembler and hashing techniques that became an integral part of computing. It was hard to make Wheeler publish something. He understood that his ideas would be picked up by graduate students and colleagues and spread throughout the university and around the world. He wasn’t interested in copyright, it was only important for him to share his ideas for the sake of technology development. The main innovation of EDSAC 2 was the use of microprogrammed control. Some commands could be compiled from a set of microoperations that were included in permanent memory. EDSAC 2 was put into operation in 1957 and the machine worked until 1965.

New technologies and algorithms

In 1960, it became clear that the demand for computer usage was increasing in the university. Thus, they needed one more. Initially, they wanted to order an electronic calculator from the University of Manchester, but it cost £2 million. The management of the laboratory concluded an agreement with the Ferranti company and purchased the Titan computer for £100,000. It was made under the condition of its modernisation and the creation of a new machine, the rights to which will belong to the company. Wheeler worked at all levels, including hardware and software.

In the 1960s, the development of computers on an industrial scale started to increase and the university laboratory could only engage in scientific research. In the 1970s, the CAP Computer Project with a new hardware system was launched in Cambridge. Its newly introduced microprogramming unit and a large number of auxiliary functions greatly accelerated the operation of the machine. In 1975-1977, Wheeler developed the local area network known as the Cambridge Ring. It guaranteed perfect transmission of the data packet within the network and was resistant to failures. However, it didn’t meet commercial expectations. Therefore, the research was stopped in 1980 and the model began to be used as a server.

In the 1980s, Wheeler became interested in algorithms and their implementation. Two of them, namely the Burrows-Wheeler transform and the Tiny Encryption Algorithm, became basic in computer science.

The latter had a significant impact on the development of the Internet. In his further work, Wheeler developed a bulk data encryption algorithm that enabled the encryption of an entire message in one process. David Wheeler believed that encryption was a basic human right and the code was freely available for a long time.

The professor retired in 1994 but continued to develop new algorithms and hold seminars. He developed a personal spam filter and researched the use of probability theory for an Internet payment mechanism.

In 2004, the scientist had a heart attack, from which he never recovered. All of Wheeler’s works are called a collection of small works of genius. The main rule of his life and research was to focus on the work process, not the result.