British scientist Francis Aston holds a significant place in the history of science, having earned the highest honor in his field: the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. His research into isotopes—variants of chemical elements—and his invention of the powerful mass spectrograph opened up a new understanding of the natural world. Find out more at birmingham1.one.

Childhood, Education, and Early Scientific Achievements

Francis Aston was born in Harborne, a suburb of Birmingham, in 1877. He grew up in a prosperous farming family, where his father, William, and mother, Fanny Charlotte, created a supportive environment for his development. In his father’s farm buildings, the young boy was drawn to various tools and began creating his own mechanical devices from discarded parts. His mother provided his initial education and taught him to play the piano, violin, and cello. His musical abilities were so remarkable that, as an adult, Francis gave concerts in Cambridge. From 1889 to 1891, he attended the local parish school and later enrolled at Malvern College, where his talent for the natural sciences became apparent. Francis continued his education at Mason College, which gained university status as the University of Birmingham in 1900. There, he was fortunate to be taught by distinguished scholars, including physicist John Henry Poynting and chemist William Tilden, who noticed the young man’s abilities and welcomed him into the scientific community.

In 1898, Aston received the prestigious Forster Prize and studied the compounds of tartaric acid, publishing his first paper on the subject in 1901. However, the scholarship didn’t cover all his living expenses, so Aston took a job at a local brewery.

Scientific Work in Birmingham

After a time, Francis found himself drawn back to scientific research. He returned to the university as an assistant to his former teacher and Fellow of the Royal Society, John Henry Poynting, helping him conduct experiments. Aston was fascinated by the electrical conductivity of gases, especially at low pressures. The late 19th century was a golden age for the natural sciences, marked by new discoveries. Scientists in Birmingham paid special attention to gas discharge tubes, which British scientist William Crookes had improved, leading to a new perspective on the properties of natural elements. Using these tubes, Crookes observed an unknown “dark space” and experimentally confirmed the existence of helium on Earth. Francis studied his work but focused his own research on how electric current and gas pressure affected the thickness of the “Crookes dark space.” He filled a tube with hydrogen and discovered a new phenomenon, which was named the “Aston dark space,” and proved that this phenomenon also occurred in an atmosphere of helium. It’s worth noting that the term “dark” in this context was used by scientists for new phenomena that were observed but not yet understood. In 1909, Francis Aston began lecturing at the University of Birmingham, and in 1910, he was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree in Applied Science. He did not defend a traditional thesis; instead, he earned his degree through practical demonstrations of solutions to new scientific challenges.

Research in Cambridge and the Nobel Prize

This new approach to studying the behavior of gases caught the attention of prominent scientists. In 1910, J.J. Thomson, already a Nobel laureate in Physics for his “investigations on the conduction of electricity by gases,” invited Francis Aston to collaborate with him at Cambridge University. In 1912, Thomson built the first mass spectrograph, which Aston modernized in 1913. Initially, the device recorded the mass spectra of molecules like oxygen, nitrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and phosgene. In 1913, it detected the isotopes of neon. Thomson tasked his assistant with improving the instrument. While assisting the Nobel laureate, Aston improved the gas discharge tube and created a device for photographing ion tracks. He later invented the method of gaseous diffusion, based on the different diffusion rates of particles with different masses, and constructed a quartz microbalance sensitive to one-billionth of a gram. The First World War interrupted his scientific research, and Francis had to work at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, where he improved aircraft coatings for extreme atmospheric conditions.

In 1919, Francis Aston returned to his research, but the microbalance did not yield the desired results. The young scientist ultimately went back to refining the mass spectrograph. He assembled a new, exceptionally powerful measuring device for its time, which had high resolution, and began studying isotopes. Using his new instrument, Aston discovered that almost all elements have multiple isotopes. He presented the compositions of chlorine, mercury, helium, argon, fluorine, phosphorus, and other elements to the scientific world, precisely determining their masses. In the process, Aston formulated the “whole-number rule,” which proposed that the masses of atoms are always expressed as whole numbers relative to the mass of oxygen. With his apparatus, he discovered 212 naturally occurring isotopes of various elements.

Following these exceptional results, the scientist was elected a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. In 1922, Francis Aston was awarded the highest scientific honor—the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his invention of the mass spectrometer, his discovery of a large number of non-radioactive isotopes, and his formulation of the “whole-number rule.” In his Nobel lecture, delivered on December 12, 1922, Aston explained the stages of the mass spectrograph’s invention, its technical “evolution,” and the imperfection of the whole-number rule. This imperfection was linked to the conversion of hydrogen into helium, a process where a fraction of its mass was destroyed. It was in this speech that he introduced the concept of “mass defect,” which confirmed Einstein’s principle of mass-energy equivalence. Using his experimental data, Aston constructed a “packing fraction curve,” which made it possible to determine whether energy would be absorbed or released in a nuclear reaction. These calculations later aided other scientists in the development of the nuclear and hydrogen bombs. In 1927, Francis designed a new, more powerful mass spectrometer, which he radically improved in 1935, allowing for even more precise measurements of deviations from whole numbers.

The Passions of Francis Aston

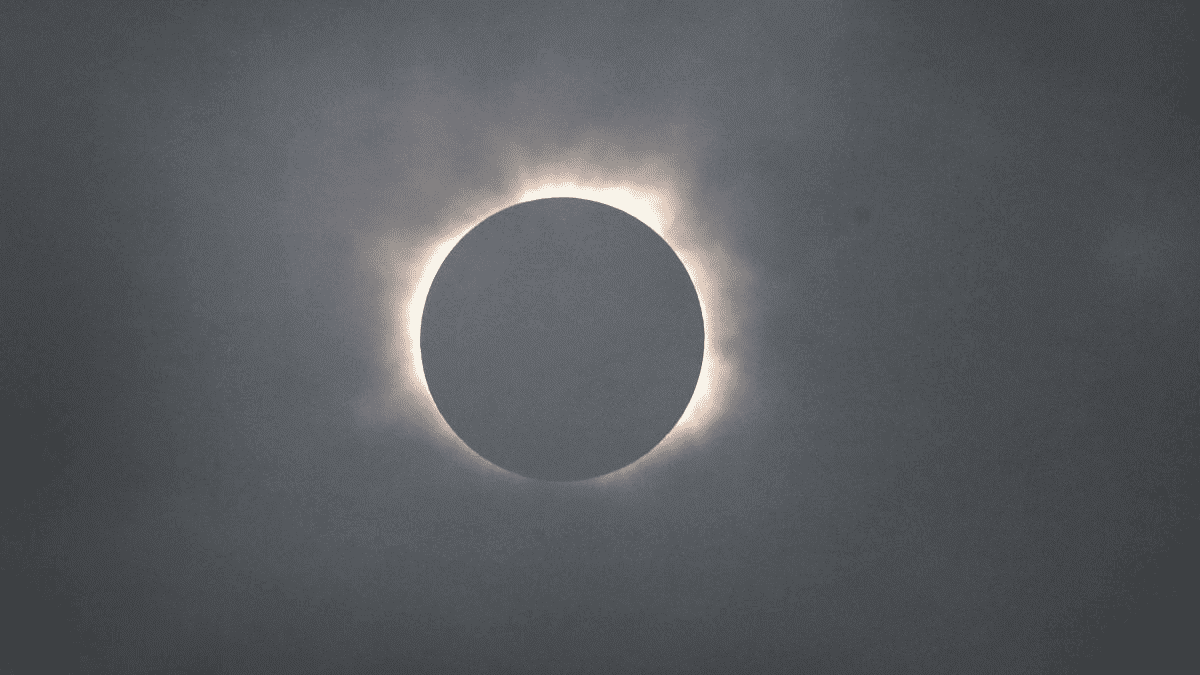

As a great scientist, Francis Aston needed physical activity to balance his intense mental work, so he dedicated his free time to sports. He was captivated by skiing, skating, and mountaineering, making regular trips to Switzerland and Norway. In the summer, he preferred cycling and swimming, and he also loved to play golf and tennis, once even winning a tournament championship in Wales. After motorized transport appeared, Francis built his own internal combustion engine and participated in car races in 1902-1903. The scientist was also drawn to travel. He visited Australia and New Zealand in 1908, and in 1909, he went to Honolulu, where he took up surfing. Photography was another of his hobbies, and it was this passion that led him to create a camera for capturing the tracks of isotopes. Despite his primary work being in physics and chemistry, he loved astronomy and participated in expeditions to study solar eclipses in Sumatra, Canada, and Japan.

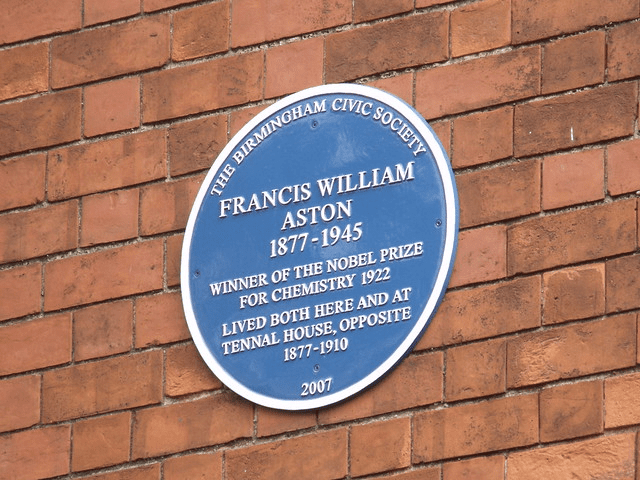

In 2007, a memorial plaque was installed in Birmingham for Francis Aston, the renowned Nobel laureate, as an expression of respect and gratitude from the local community.